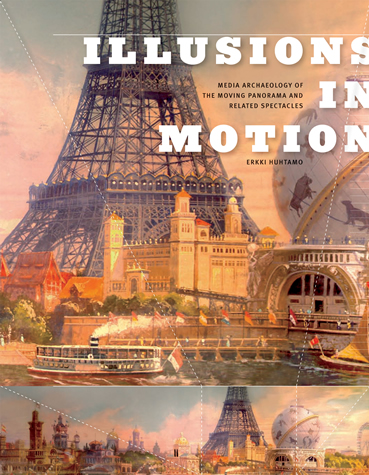

Author: Erkki Huhtamo

Author: Erkki Huhtamo

Publisher: MIT Press – 438 pages

Book Review by: Krishnan Ramamurthy

Still and moving panoramas of many types that were created in the nineteenth century are the subject of this unique book by Errki Huhtamo, a professor in the Department of Design Media Arts at the University of California in Los Angeles. In simple terms, a panorama is a form of visual story-telling.

Huhtamo is described in this book as a media historian and a media archaeologist. If you do not know any media historian or media archaeologist, you are about to meet one, if not personally – so you can ask questions about his profession – then at least virtually.

This large book is – I will be frank – not an easy read, basically because it deals with a subject that I am unfamiliar with. But I shall explain the contents of this book as best as I can, keeping this limitation in mind.

First of all, there is a lot of content – images and writing – in this book printed in small fonts. And its content is varied in nature, so this review is not going to be easy to do, to say the least. It took Huhtamo more than 25 years to research and gather the immense amount of material that forms the basis of this work of 438 pages.

Secondly, it involves finding definitions for and getting familiar with concepts such as “media archaeological methodology,” and “media cultures” and “moving image media of the nineteenth century” (not movies) and “moving panoramas”.

We turned to comments on this book by experts to get a start on understanding the phenomena that are covered in this book.

For example, Douglas Kahn, research professor at the National Institute for Experimental Arts at the University of New South Wales in Sydney writes that “Illusions in Motion informs an extraordinary, rolling range where painting meets architecture meets theater meets cinema that scrolls into all the screens, immersions and augmentations of today.”

Kahn relates this book to media archaeology by stating that it is “a massive archaeological dig revealing a long lost city that we still inhabit. With a quarter century of focused, original research in numerous languages, it sets the scholarly standard for media archaeology, a historical enterprise that gauges itself on relevance to the present.”

Tom Gunning, a professor in the Department of Cinema and Media Studies at the University of Chicago, writes: “In this exciting book, Errki Huhtamo, our foremost media archaeologist, gives us the most thorough and insightful treatment of the moving image media that dominated the nineteenth century and gave us a new word for a modern mode of vision: the panorama.”

A deeper understanding of panoramas – the main subject of this book – comes from reading The Formation of a Panaromaniac in the author’s Preface. In it he poses the question to you: Why would anyone spending many years of his life writing the book you have in your hand?

He relates to us how his interest in panoramas began in the 1980s when he studying cinema and the cultural history of media and technology. He goes on to write that his curiosity about panoramas grew out of his larger interest in optical spectacles.

Panoramas have existed for a much longer time than moving pictures. They were around for more than a century before moving pictures were recorded on celluloid or film.

This book has pictures of many kinds of panoramas. Stationary (sometimes called still or unmoving) panoramas were the first ones created in the nineteenth century, which were followed by moving panoramas. The book describes how panoramas evolved from a stationary to a mobile medium.

The painted, performed and the discursive panorama are three other types of panoramas. There is also the peristrephic panorama. Circularity, stasis and motion are three concepts discussed in the chapter on this type of panorama. The book also discusses other types of panoramas such as the balloon panorama, the diorama and the myriorama.

If you would like to truly understand panoramas very well, my suggestion to you is to get this book and look at the pictures of the different types of panoramas. As they say, a picture is worth a thousand words. This saying is especially true for this book.