Author: Gregory Smith Simon

Author: Gregory Smith Simon

Publisher: New York University Press

Book Review by: Sonu Chandiram

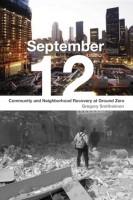

Adjacent to the World Trade Center disaster site in Lower Manhattan where about 3,000 people lost their lives on and after September 11, 2001, is a well-planned and well-designed neighborhood known to New Yorkers as Battery Park City. In it live some of the wealthiest people in New York City. The Census of 2000 showed nearly 8,000 residents there, with 75 % Whites, 18% Asians, 5% Hispanics, and 2% Blacks.

Battery Park City, as described by the author of this eye-opening book, sociologist Gregory Smithsimon, is a 92-acre “comprehensive, state-planned (and state-subsided) development project of luxury apartments, financial sector offices, parks, stores, schools and museums that were tucked to the side of the Financial District, stretching in the shadow of the Trade Center for a mile along Lower Manhattan’s Hudson River waterfront.” Among other features, this area has a lots of trees and free spaces for people to walk around, like its waterfront promenade.

Not much was covered in the mass media about this neighborhood and its community of residents in the immediate aftermath of that horrific terrorist attack. The immediate focus then was on getting the news out on the who, what, when, where, and how of that plane-bombings on the buildings, their collapse and the rescue operations that followed.

And except for the October 15, 2001 Newsweek cover story by Fareed Zakaria on the why aspect of this massive terrorist attack, not much else attention then was placed on understanding the reasons behind it. (And over all the years since September 11, 2001, the U.S. mainstream mass media has not bothered to deeply examine the ‘why’ nor has any U.S. president taken any action on the psychological aspect if its prevention, e.g. by consultation with Arab leaders who understand terrorists well).

The large amount of rubble at the vast site was eventually cleared, and life moved on after the catastrophe, and more attention was placed on building an appropriate memorial for the victims than doing a post-event analysis and deciding what diplomatic and other such actions needed to be taken to prevent further attacks of this scope.

When public discussions began much later about what type of memorial should be built for the victims, where it should be located and other details, the Battery Park City residents brought ‘strikingly different priorities’ than the family members of those that were killed, according to an NYU Press description of this book.

The author writes that Battery Park residents “saw their difficulties as distinct from those suffered, for instance, by the families of both civilians and rescue workers killed in the towers, and could neither accord space for other sufferers, nor find common ground in which to recover.”

Battery Park City residents enjoyed the spirit of community that existed there, where interaction like conversing with neighbors was possible in the quiet parks and other open meeting places in that semi-isolated ‘suburb in a city’.

But they felt threatened, and feared that their seclusion from the rest of Lower Manhattan would be intruded upon, and ripped away from them by the redevelopment plans for Ground Zero, which might lead large numbers of people from New York, tourists from the rest of the U.S. and foreign countries to ‘invade’ their community and take away their quiet enjoyment and peaceful life in their neighborhood.

In my view, certainly both groups of people – Battery Park City residents and victims’ families – had rights to express their feelings that had to be taken into account in making decisions relating to the memorial site that was to be constructed.

The family members had varied opinions of how their late loved ones should be remembered. And the nearby residents also had their own views on what should be built because they lived there, worked there, and passed by there.

Many of us have wondered why it took over a decade after the disaster to build a memorial site in the area, and part of the answer lies in the lengthy discussions that ensued, the consideration of the numerous proposals and designs, and the decision-making in the selection process that preceded the construction.

In his conclusion, the author writes that Battery Park City is a success. Within the larger adjacent, impersonal city with tall skyscrapers and the hustle and bustle, was created a secluded community wherein people can go nearby places of worship, enjoy shopping, and peacefully raise their children who can go to nearby schools, and most importantly, where there is personal interaction and a spirit of community and belonging.

This is well-researched book by someone who understands neighborhoods and their effect on people. It is an insightful and unusual book well worth reading. Gregory Smithsimon, is a professor of sociology at Brooklyn College. He is the co-author of The Beach beneath the Streets: Contesting New York City’s Public Spaces.